CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH THE EYES OF A POLAR EXPLORER

On the 13th January I gave a key note lecture to an audience of over 700 students and faculty at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia on climate change. Some of whom are leading figures in climate science.

This topic is so important that I'm making the transcript of my talk available for all to read.

It was a really warm day…

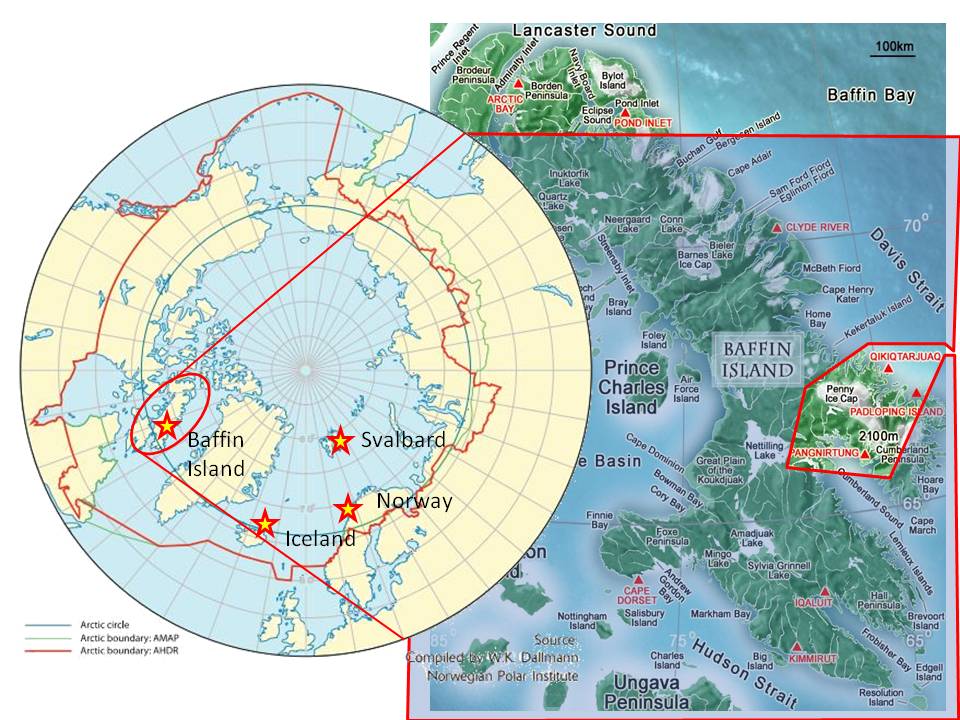

...in the Arctic. We were at the start of our expedition to cross the Penny Ice Cap on Canada’s Baffin Island and the -10 to -15 Celsius we had that day was the best we could hope for.

This was my third expedition to Baffin Island and my sixth into the Arctic Circle. The other three expeditions being on the European side in Svalbard, Arctic Norway and Arctic Iceland.

Baffin Island is the fifth largest island in the world and sits almost entirely within the Arctic Circle. Despite being twice the size of the UK, Baffin Island is home to only 11,000 inhabitants, most of them Inuit, making it one of the most sparsely populated places on Earth.

Our expedition was attempting to open up a new route crossing the Penny Ice Cap, said to be left over from the last ice age. We were also trialing several remote learning techniques developed by my team mate Antony Jinman for his organisation Education Through Expeditions. Through the use of satellite communication we had direct contact with a number of schools in the UK who could from the comfort of their classroom ask us questions about the environment, what we did that day and how we survive in the Arctic, which, in turn, we could answer from the 'comfort' of our tent.

We flew into the Inuit community of Qikiqtarjuaq, home to 500 people, and hopefully all being well would end up, at the end of the expedition, in the southern community of Pangnirtung where we could fly out from. At the start of the expedition we are transported out by snowmobile by our Inuit outfitters to our predetermined start point, closer to the ice cap. They would then leave the three of us and all our equipment, food, and fuel and return back to their community – generally the Inuit think we’re mad for embarking on such expeditions. However it is the long journey on the back of a snowmobile that I don’t like the most: The windchill is excruciating!

But the scenery more than makes up for it.

We traveled past massive icebergs, halted in their voyage south by the freezing seas. They towered stories above us, dwarfing us in their majesty. We stopped in awe and the silence that followed was deafening. We passed seal holes, where, some way in the distance, a sun bathing seal quickly dropped down through their hole into the safety of the sea as they heard our snowmobile approaching. Arctic hares raced past us, somehow managing to maintain the same speed whilst shooting up a 50 degree mountain snow slope. We witnessed the extraordinary shapes created by pressure ice as the sea froze, forcing us to weave in and out, up and down, to find the easiest way through.

And then we came across these footprints.

There is only one animal in the Arctic that can make footprints as large as these: The polar bear.

You can see how large the prints are in comparison to my hand. As well as the larger set of prints down the middle you can see two smaller sets either side. They were, undoubtedly, of a mother and two young cubs. The footprints disappeared off into the same direction as we were heading.

And so it wasn’t long before we came across the bears, just as we suspected: A young family. But our noisy snowmobiles spooked the mother. She sprinted off and her cubs ran hard to keep up.

We stopped and watched.

But one of the cubs was falling behind.

He fell so far behind that he stopped and absolutely confused about what to do he turned around, barked, and started running towards us.

I could see his breath as he trundled across the snow towards us. It was the cutest thing I have ever seen but also the most heartbreaking. The young cub absolutely lost.

It was decided that we would have to intervene.

We used the snowmobiles to chase the bear in the right direction, which worked, partially. He did find his mother’s tracks and started to follow them, but he was moving slowly and his mother hadn’t waited, she was kilometres away.

Eventually Billy, our Inuit outfitter decided that we would have to intervene further. We would have to catch the bear and take it back to the mother ourselves!

We used the snowmobiles as pincers to close off the young cub’s path before jumping out and trying to catch him.

But his teeth were sharp and his claws were long and he definitely didn’t want to be caught.

I managed to capture the end of this adventure in a short video:

It was a massive relief for us to see the family reunited, to see them trundle off together on the hill side behind us.

We were now many hours behind schedule on our first day though, and low on fuel. Only by cannibalising the fuel and abandoning one of the snowmobiles did we manage to get to our start point. As we quickly set up camp in the fading light of the day, Billy and Charlie embarked on their long and cold journey through the night to return to Qikiqtarjuaq. We were now at the start of the expedition.

Billy our Inuit outfitter who was responsible for dropping us off that day when we encountered the polar bear and had that dreadful journey back in the nighttime, says that in the village they are seeing a lot more polar bears than ever before.

Scientists who have been studying polar bear populations however are becoming increasingly worried about polar bears and their future. Which one of these is right? Bizarrely they both are, but that is not good news for polar bears.

Polar Bears are highly adapted Arctic Predators, an evolutionary process which has developed over thousands of years

- Dense fur means no exposed skin. Each hair of their fur is hollow, trapping the maximum amount of air.

- A thick layer of fat gives warmth and buoyancy during swims in the cold, arctic sea.

- Huge feet disperse their weight and bumpy footpads aid grip so that they can walk and run over the slippery sea ice. These feet also make great paddles for swimming.

- Strong and powerful limbs allow them to run and outpace seals.

- A narrow skull combined with long, strong neck muscles and sharp teeth enable them to be bold predators, plunging through snow holes headfirst to find seals with the incredible strength to pull them out.

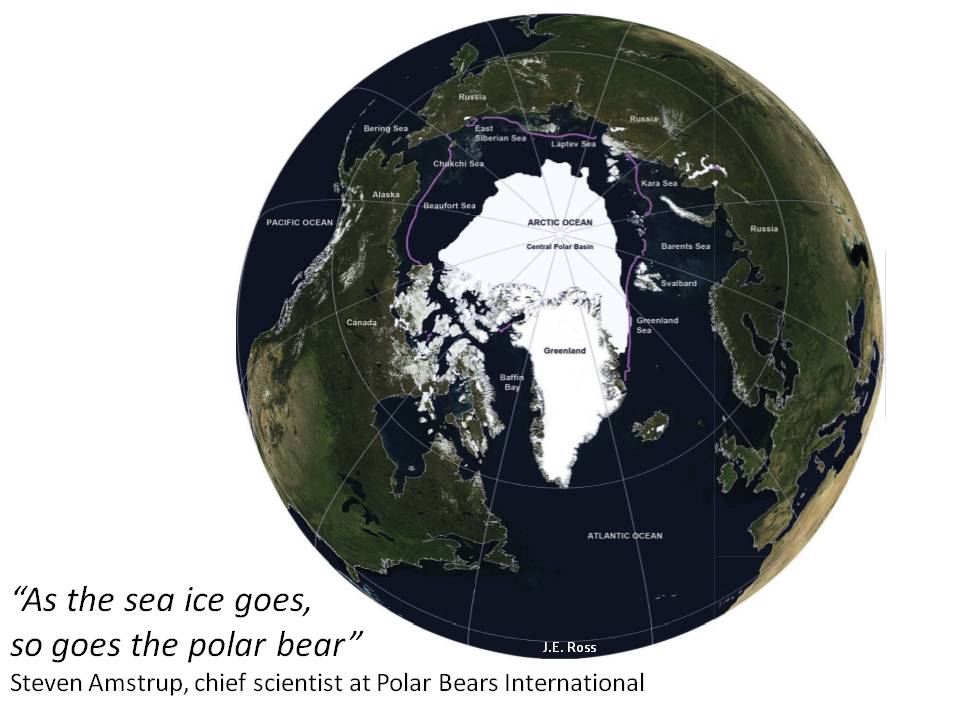

Polar Bears depend on sea ice to move around their habitat and hunt their primary source of food; seals. They use the sea ice for tracking a mate and for breeding. They survive on land only by utilising fat reserves they have built up during a successful season of hunting.

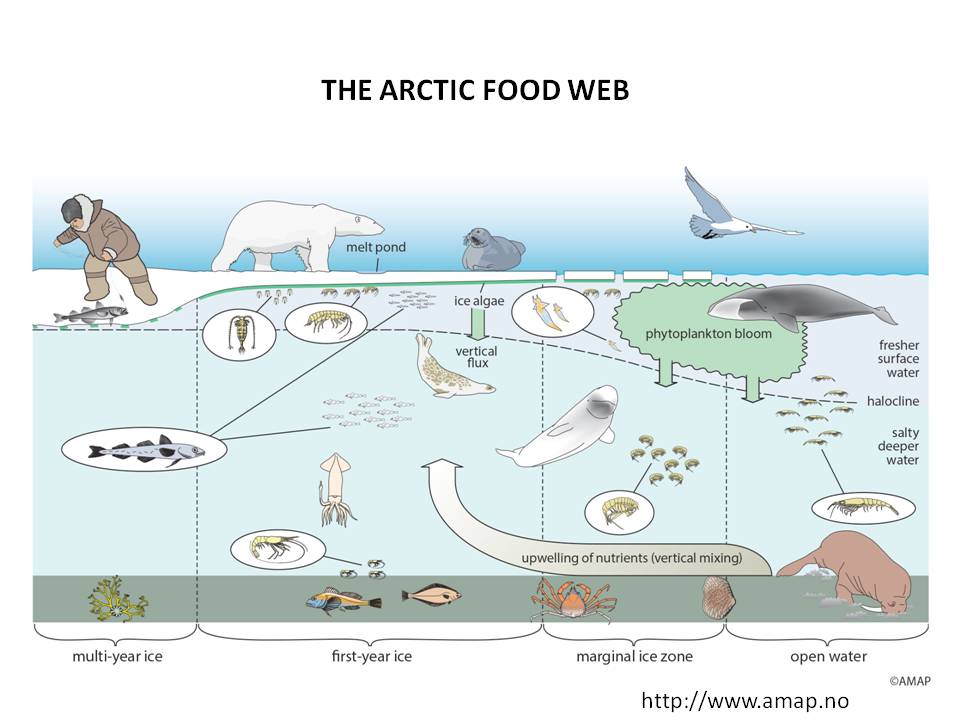

But the sea ice is far more important than just for the polar bear.

Sea ice is the enabler for the entire arctic ecosystem which the Polar Bear reigns as a top predator.

Sea Ice acts as “upside-down soil” where on the underside of the ice, algae and other photosynthetic phytoplankton can grow. This is fed on by copepods and other zooplankton, and this is the food source for arctic cod. Arctic cod is a key food source for almost every other arctic marine mammal, from the beluga whale and narwhal, to almost every arctic seal species.

In short, without the ice, there is no cod. Without the cod, the entire food chain breaks down. So the ice plays a pivotal role in initiating the arctic food web, generating food for all wildlife in the Arctic Ocean.

And the sea ice is disappearing. Pictures taken periodically from NASA satellites show a reduction in sea ice of 13.3% per decade since 1979. (1)

In September 2012 the total volume of arctic sea ice calculated by scientists plummeted to a stunning new record low that was a mere 20% of the ice volume existing in 1979 (2). It is beyond comprehension how fast the sea ice is disappearing.

It is estimated that due to this rate of melting, the Arctic will be sea-ice free in the summer time by the mid-century.

Source: J.E. Ross

The ice is disappearing because of increasing global temperatures due to climate change. The Arctic is at the forefront of climate change and experiences temperature rises far higher than global average levels.

Surging carbon dioxide and methane levels have pushed greenhouse gases to record highs in the atmosphere. This instability in our atmosphere is causing our climate to change.

A recent study (3) compares green house gas levels in the atmosphere today with the last time in history when they were at a similar level. The last time that they were at a similar level was 2.7 million years ago (2).

The study found that at that time sea levels were 20m higher than today. That could very well be the new equilibrium that our world will settle in.

Many of the most populated areas in the world would be completely under water in this scenario.

This won’t happen overnight or in our lifetime, but the inertia of the world is such that if we want any chance in preventing this from happening, the window for change will close within the next few years.

And so, with the sea ice disappearing, Polar bears are being forced to come onto land looking for food. Sadly their keen sense of smell brings them to human communities and villages and in particular the rubbish dumps leading to greater conflicts between man and bear. In such conflicts it is the bear that comes worse off.

[Many thanks to Silverback Films for allowing the screening from their recent documentary ‘The Hunt – Episode 7’ - can be found on BBC Stores]

The expedition to cross the Penny Ice Cap took us 19 days on the ice across the Auyuittuq National Park - which means The Land That Never Melts.

The top left photo shows how the inside of our tent looked like some mornings. We had to build snow walls each night to protect us from being blown away or our tent destroyed, and we had to ensure all of our skin was covered to protect us from the elements. But we were almost there, we had made it to the last day of the expedition and we would soon be arriving in the village of Pangnirtung with people, civilisation and, hopefully, a hot shower!

But we woke up that final day in a blizzard!

The whiteout disorientates and confuses. With no reference points or even the shadows of the sun to distinguish ground from sky we had to rely solely on our compass for direction.

But we were motivated, we would soon be in Pangnirtung and slowly but confidently we continued.

But 6km from the Inuit community we came to an area where the snow was wet. I looked behind and saw my tracks fill up with water. This can only mean one thing – Thin Ice!

I was ahead, so I tested the ground first, by stabbing hard with my poles before stamping down with a ski whilst supporting my weight on a safe area. It was solid enough. It was not clear whether this area was local or extended – in the white out we had no reference. I moved tentatively onto the ice which held my weight well, and changed my direction to try and find my way onto thicker ice.

I had not advanced more than 100 metres before I heard shouting behind me and the dreaded sound of ice cracking. I whipped around to see Antony, seemingly okay, but where was Duncan?

Twisting myself to look down, I saw a broken section of ice and Duncan in the middle of a black opening. He had cracked through the thin ice, dropping him, skis and all, into the freezing waters beneath. His pulk fortunately was still on the ice, far enough behind him to not fall through and drag him under.

He had to get out of the water fast. The freezing waters would have penetrated his clothing and would be cooling him down fast. The best solution was if Duncan could drag himself out of the hole and onto the surrounding ice, if we approached the weakened place we could all fall in – making this dangerous situation into a complete disaster. Time was of the essence, as it would only take a couple of minutes before he became too cold to help himself.

Whilst Antony prepared the rope for a possible extraction I encouraged him to get out fast. After getting over the initial shock he moved to the free edge of the hole. We watched as he used his arms and poles on the ice, clawing to gain purchase and started to haul himself out. He was heavily burdened by his skis and heavy water laden clothing making the task even more difficult. The ice broke up under his weight and the hole opened further. Rallying himself further he pushed through to the newly formed edge. Again it broke under his weight. His strength would be fading by now. We shouted at him, over the blizzard, to try another part of the hole, this time it held and he was finally on his hands and knees, next to the hole.

Even though he was out of the water and the immediate danger had been averted we were still on perilous ground. How weak was this area? How far did it stretch? And meanwhile Duncan was becoming colder and colder. The wind and snow buffeted us, whipping the heat from his soaking wet clothing. And there began the most testing skiing of the expedition.

We were surprised by having found the ice so thin at that time of the year. Melting of this part of the sea ice should not have started so early and it should’ve been completely safe to ski into Pangnirtung without a situation like this occurring.

But due to the melting of the Arctic this is the new reality that we will all have to get used to.

Due to the melting of the sea ice, one of the most sought after rites of passage for explorers, the skiing to the North Pole from land is becoming increasingly impossible. It is literally traveling over thin ice. There were no attempts in 2015, and it is unlikely there will be any attempts this year. Will there be any other attempts ever again?

There are two very important things that we shouldn’t forget when considering the melting of the Arctic.

- What is happening in the Arctic is happening everywhere... These large changes that are happening in the Arctic, on the forefront of climate change, are happening more or less everywhere, whether we have monitored it or not.

- That this world is interconnected and what is happening in the Arctic is affecting elsewhere.

To see in the New Year I went on holiday to the North of England, but it was underwater. In early December a storm passed through bringing torrential rains, a ‘once in a hundred’ year event it was said. The rains were so fierce they destroyed flood defenses and broke the river banks to flood towns and cities across Northern England.

A week later more rain came, and a week after another storm passed through and flooded the same area again. This pattern continued right into the new year bringing misery and danger to thousands of people.

It came as no surprise when December was recorded as the wettest month in Britain since records began! (4) But It’s pointless talking about excessive and unprecedented weather, because each year, as the climate warms, it gets worse and worse. If a rich country like the UK struggles to copes with the very beginnings of climate change, how can anyone else?

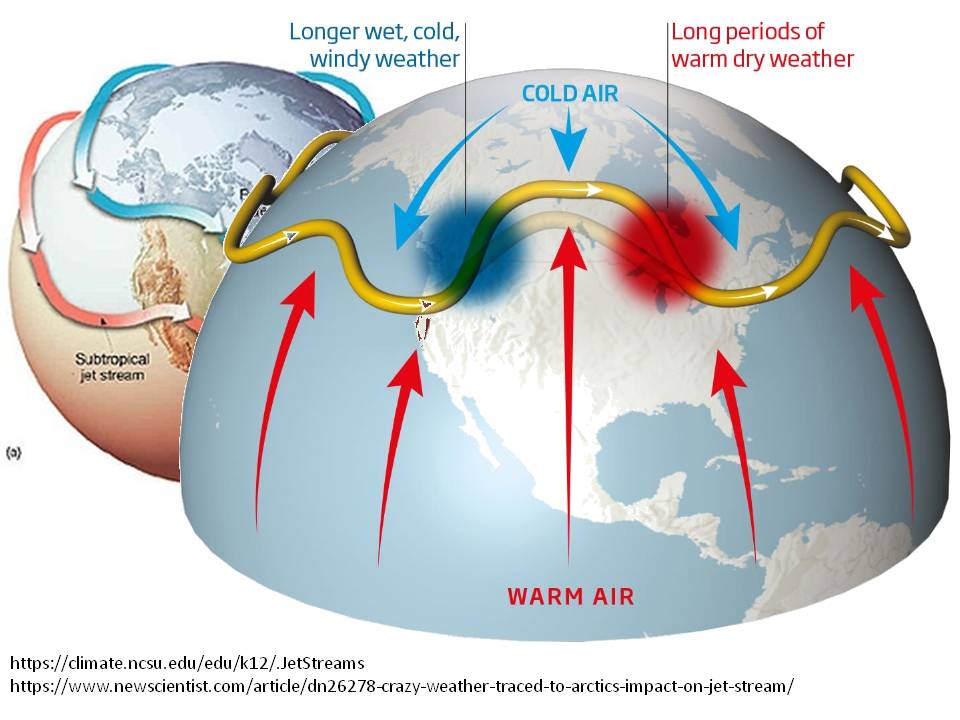

The reason why these floods happened can be linked directly to the loss of Arctic sea ice due to changes in the Jet Stream.

The jet stream is the principle means that weather systems are transported around the globe from West to East. Essentially they are rivers of meandering wind. One of the most important factors influencing the strength of the Northern Hemisphere or Polar jet stream is the large temperature differential between the warm tropics and the cold Arctic. When the Arctic is very cold and the tropics are very warm there is large temperature differential and the jet stream is fast and powerful and these meanders are very slight.

However when the temperature differential is small by, for instance, a warmer Arctic, due to climate change, then the jet stream is slower and weaker and the meanders are far greater. These larger meanders lead to a greater probability of extreme and prolonged weather events such as the flooding that we have experienced in the UK last December.

These events will occur more and more frequently as a result of green house gas emissions. This is the new reality that we have to live with.

The Middle East won’t be exempt either. A recent study (5) has assessed how extreme heat waves will become more and more dangerous if unmitigated climate change is free to continue. The study assessed a particular condition: When temperatures rise above 35C in very humid conditions the body can no longer sweat. Sweating is the primary method by which the human body regulates its internal core temperature and without the ability to sweat it would prove to be lethal to stay in an unprotected environment. This extreme heat condition has never happened since records began according to the researchers, but what the research has found is that towards the end of the century large parts of the Middle East could face these extreme events including Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Doha.

Rich countries such as Saudi Arabia can afford to keep all its citizens in air conditioned and protective environments but poorer regions and countries could become uninhabitable.

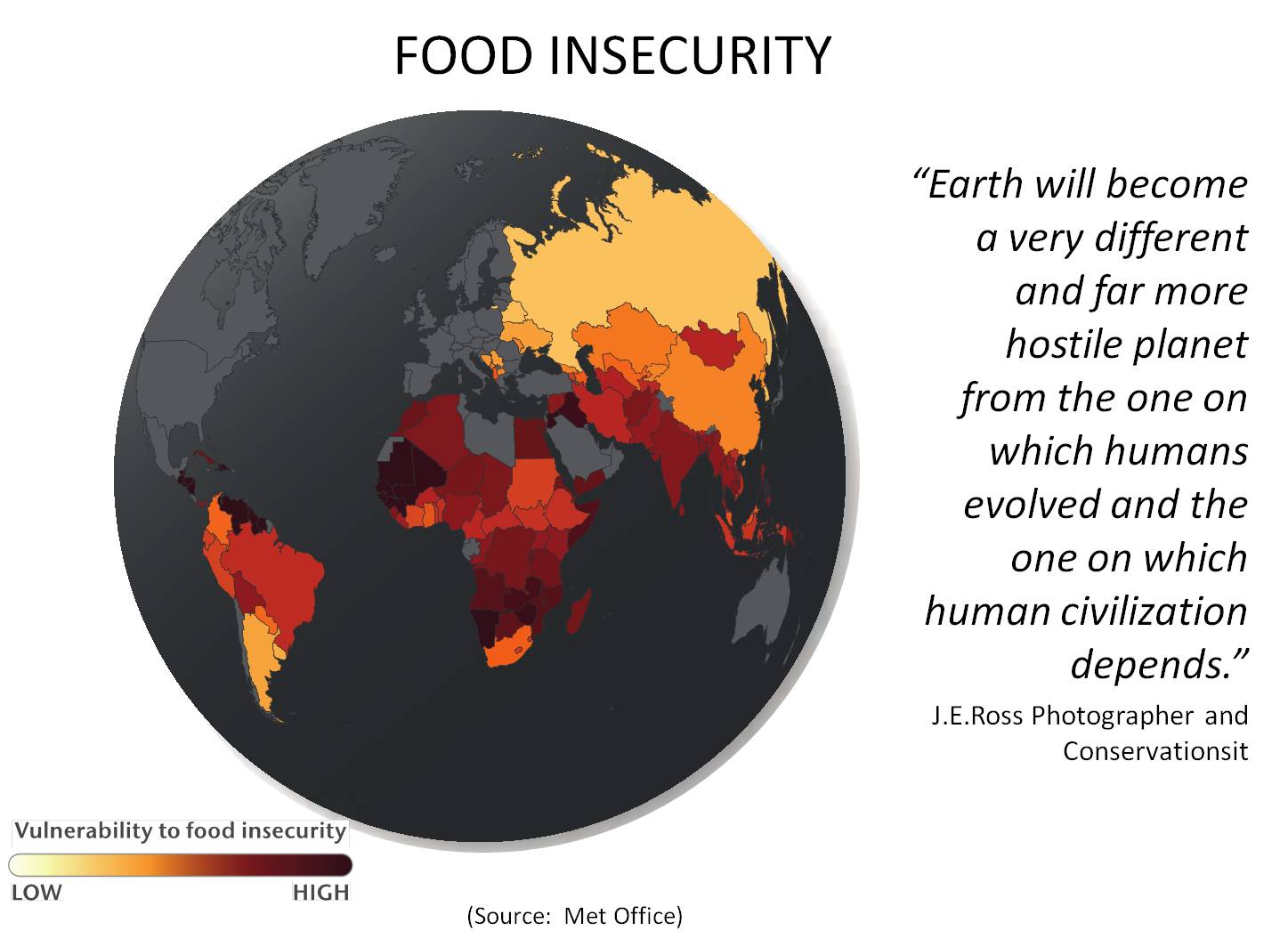

Due to these increased likelihood of floods, droughts, heat waves and all manners of extreme weather events there will be a greater chance of failed crops and food scarcity. The planet above shows the world as it is now with the food insecurity running from light beige to a dark brownish red. The areas greyed out are deemed to be rich enough to not become affected by food insecurity – for now.

The graphic above shows a projection of how the world would be in 2080 if we just carry on as we are, without making the drastic changes needed, in the ‘business as usual’ scenario. Africa and south Asia will be heavily impacted, with South America following shortly behind. The poor are the most vulnerable and this will undoubtedly lead to more conflicts and mass movements of people greater than anything we have seen before, environmental refugees in their millions.

It is clear that from every angle that we view it, climate change is going to have major negative impacts on our lives. And in many areas, people and wildlife are already suffering. We have to agree to do something now.

And we have agreed to do something. In December last year 190 countries decided at the Conference of Parties (COP) 21 in Paris to act on climate change. All 190 countries agreed to limit global warming to 2C above pre-industrialised levels.

The first graph above shows the global average temperature normalised to the temperature in 1850.

The red line shows what would happen if we carry on in the ‘business as usual’ scenario. By the end of the century temperatures will rise globally by six degrees Celsius on average. In the Arctic it would be most likely be over ten degrees Celsius. The blue line shows how we can achieve the 2C limit.

This means, if we look at the blue line in the graph below, that we have to reduce green house gases substantially now, right now, this year. And continue to do so to achieve emissions by the end of the century of less than we were producing in 1850. That is whilst considering the increase in population and technology that we have in the modern age.

We have to find another way of doing all these things that we treasure so highly in modern society such as having electricity on demand, fuel for our cars and aeroplanes, heating and cooling of our homes than by creating more green house gases.

A lot of the big changes we must rely on our governments to make, such as power generation and energy production and we need to lobby them and keep on lobbying them to make such changes. But there are also real tangible changes that we can all make and that this 2C target crucially relies on.

We all know about the need to reducing the amount we fly and reducing the number of car journeys we make, but there is another industry that we can all impact on right now, every day, one that emits greater green house gases than the entire transport industry combined.

That is the livestock industry. Creating more than 14.5% of global green house gases, the livestock industry, the production of meat and dairy, is one of the primary causes of climate change and one which has to reduce for us to have any chance of achieving a 2C target. (7)

As well as carbon dioxide the unique digestion methods of livestock and in particular cattle releases huge amounts of methane and their waste produces copious amounts of nitrous oxide.

Both these gases are many times more potent in their potential as green house gases than carbon dioxide with methane about 25 times as potent and nitrous oxide 300 times as potent.

Livestock farming is also a hugely inefficient use of energy and land use. It accounts for, incredibly, the single greatest use of land surface by humans. It leads to vast tracts of forested regions to be cut down in order to grow grain for feed or pastures for grazing, further compounding and negating our planet’s ability to regulate the atmosphere.

The 2C target for limiting global warming cannot happen without a substantial reduction in meat and dairy consumption, and that must start with our own demand and consumption. (8)

By 2050, the world's population will likely increase by 35%. To feed that population, crop production will need to double. What can we do to feed the growing population and protect the environment at the same time? Watch this video to find out!

Posted by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on Wednesday, January 13, 2016

It is clear that climate change is happening at an alarming pace and will detrimentally impact all aspects of our lives, not just in the Arctic but wherever we are on this world and no one or no country will be exempt. It will disrupt our livelihoods and bankrupt our societies.

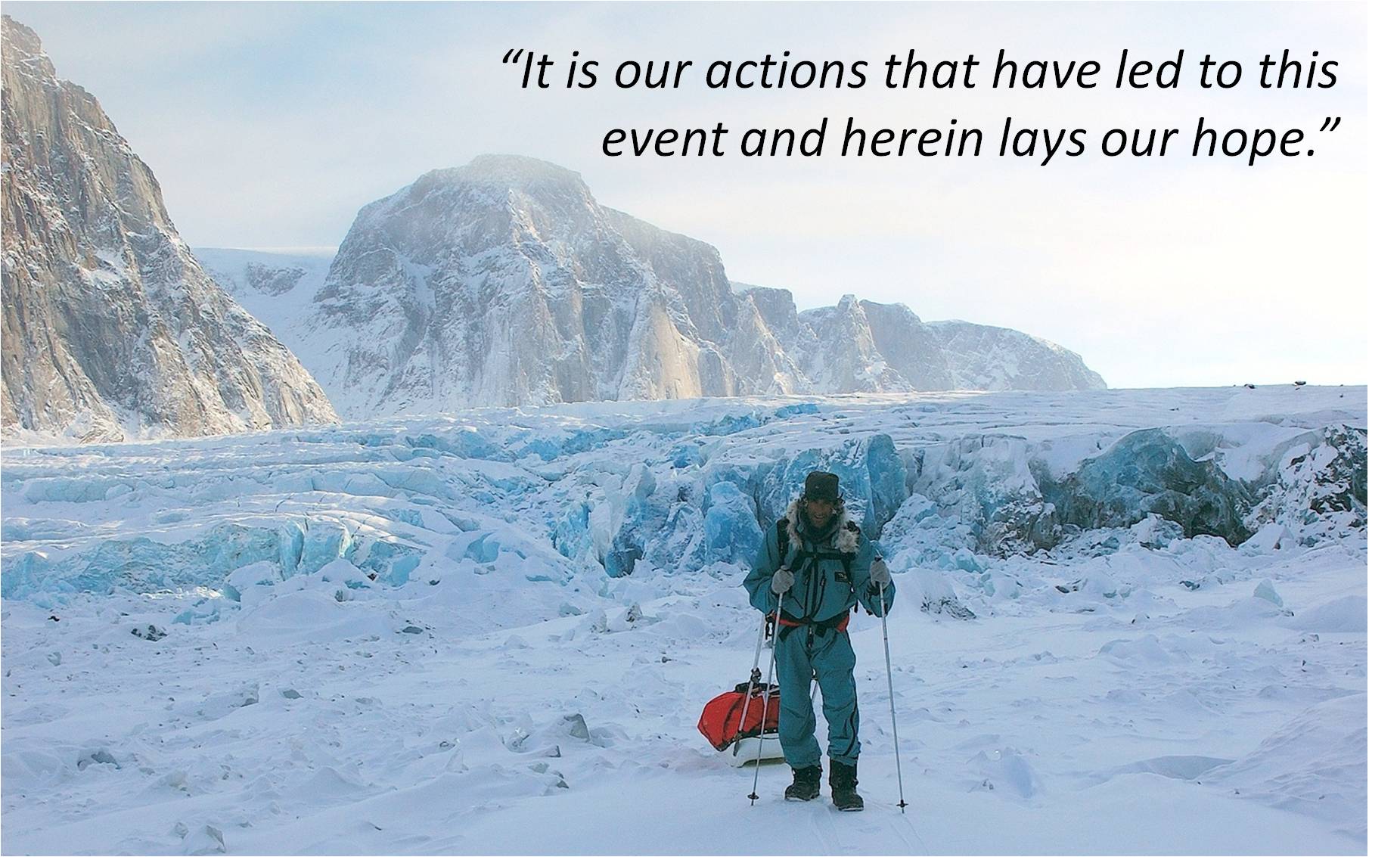

It is our actions that have led to this event but herein lays our hope.

As it is our actions that have caused this, the solution also lies in our hands. But we must act now and we must act quickly. We must do more than we planned on and we must all do this together.

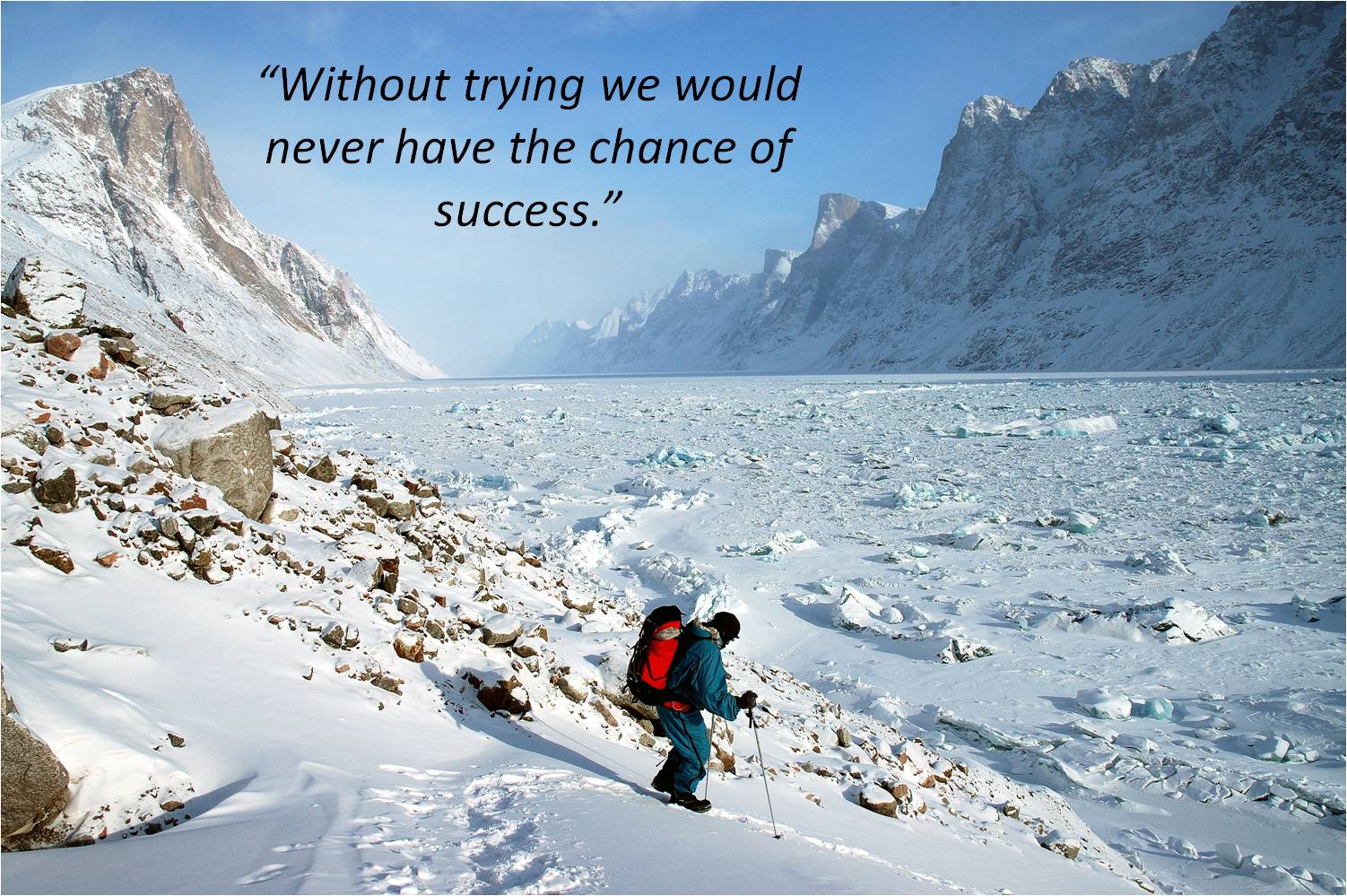

The road ahead is hard and the challenge is daunting. It appears, insurmountable. But when I really think about the challenge we are facing I’m reminded about launching an expedition.

One of the reasons we love to hear stories of expeditions to the world’s most inhospitable places is to hear how people succeed when the odds were stacked against them, where the adventurer must overcome countless obstacles put in front of him. Sometimes, though, we do not succeed. But the times that I haven’t, it has never haunted me because I know I tried everything in my power to make it succeed.

The expedition to cross the Penny Ice Cap where we encountered the polar bears and where Duncan fell through the ice was actually the second time that Antony and I attempted the crossing.

The first attempt, three years earlier, was aborted only a week into the expedition when my feet froze. We turned around and went back the way we had came from, across hard fought over miles and terrain. It was one of the hardest decisions in my life but it was the right decision, to carry on regardless knowing that I would probably lose my toes, feet and possibly a lot more would have been foolish. I didn’t feel guilty about turning around on that expedition, because I knew it was the right decision, because I knew that we had given everything we could for the success of the mission.

But without trying then we may never have tried three years later and may never have had the chance of success....

....and the views from the other side are magical!

And so we must do everything we can to change the course of history that has been foretold. We must do things differently, to find another way: individually, within the institutions that we are part of, and in the way our countries operate independently and collectively because to carry on regardless would be foolish.

I am also an aeronautical engineer and as an engineer I am in awe of the greatest exploration programme that our species has embarked on: The exploration of space. And when I think of any great challenge I turn to one of the most impassioned speeches that has ever been made.

John F. Kennedy gave this speech in 1962, to rally a nation to a goal that they saw as crucial for their survival. He vowed to send a man to the moon, within the decade. A formidable feat considering they had only sent a man into space a year earlier, here’s an excerpt of the speech.

…and they did go to the moon within that decade. In 1969, with the whole world watching, Neil Armstrong put those first footsteps onto the moon.

If one nation can rally themselves to achieve this monumental goal within a few short years then surely as a globe we can commit to reducing the effects of climate change when our very future relies on it?

In 2010 we took a group of students and recent graduates to Baffin Island, living with the Inuit and trekking 300km over some of the most spectacular scenery on the planet and one that is at the forefront of climate change.

The objective of the expedition was to develop resources for classrooms, interacting via our web platform directly with school children in the UK. I conducted a video project on this expedition asking the members and the other leaders to reflect on the environment whilst in one of the most spectacular and enchanting places on the planet and one that is being the hardest hit by climate change. But I almost didn’t get the chance to finish the video, as we almost had a disaster due to the unseasonably warm temperatures we experienced.

There are several river crossings along the path; the rivers are coming straight down from the glaciers due to the melting in the summer time. This is a completely natural process and the ice would normally be replenished during the winter months. But this summer had been unseasonably warm and we had a week long spell of temperatures over 20 degrees Celsius meaning there was a lot more melting than normal and rivers were higher and faster and crossing them became more dangerous.

This was the last river we had to cross and this picture shows the two other leaders scouting out the crossing before committing the rest of the group to it. We had woken up especially early that morning, at 4am, in order to cross the river at it’s lowest before the heat of the day melted more ice making the river higher.

The second photo shows Antony and Rachel half way across. Typically we never attempt to cross rivers that are higher than knee height as it is unlikely you can keep a stable footing and are likely to fall in. The water here you can see is just below their knees.

This was the last photo I snapped before I launched the rescue operation. The water is well up to their waists and they are struggling to keep a footing. The water temperatures are close to freezing and having been in the water for a few minutes already they would already be starting to get very cold. No sooner had I instructed the other members to form three separate teams and positioned them at various points downstream did both Antony and Rachel lose their footing and fall into the water. Their bags filled up with gallons of water that pulled them down as the river started to wash them downstream.

Fortunately having launched three separate rescue teams we managed to grab hold of them and drag them to shore before they were washed away. Antony’s legs were battered and bruised and they were both bordering on hypothermia. We made camp putting them into the tent to warm them up and filled them with hot drinks. A disaster avoided.

And so I did get a chance to finish my film and here is a short excerpt of the 2010 Climate Change film where Antony and Rachel are reflecting on why we should care about the climate.

Limiting climate change is not about saving the planet, this planet has endured climatic conditions that are far more extreme than what we are talking about, but our very evolution has been adapted for this cool period in the earth’s climate, all our advanced technologies and societies rely on it.

I would like to finish off by reiterating what Rachel said in the video. For me personally, I want to continue going into the rainforests and onto the ice caps and sea ice. But it’s bigger than that: “We need it; otherwise we don’t know how we’re going to survive.”

FURTHER READING

Some accessible articles that are a wealth of information:

Global Warming: The Arctic Meltdown. Ocean Geographic Magazine. October 2014, pp. 98-161. Author: Jenny E. Ross

Ice Bear in Trouble. Ocean Geographic Magazine. January 2012, pp. 47-61. Author: Jenny E. Ross

SOURCES

1. NASA Climate . NASA. [Online] December 28, 2015. http://climate.nasa.gov/.

2. Ross, Jenny E. Global Warming: The Arctic Meltdown. Ocean Geographic Magazine. October 2014, pp. 98-161.

3. High tide of the warm Pliocene: Implications of global sea level for Antarctic deglaciation. Miller, Kenneth G. and Wright, James D. et al. 2012, Geology, pp. 407-410.

4. Met Office. Climate Summaries. Met Office. [Online] 01 26, 2016. http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/summaries.

5. Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Pal, Jeremy S. and Eltahir, Elfatih A B. 2015, Nature Climate Change.

6. Met Office Hadley Centre. From global carbon budgets to food security. 2015.

7. Bailey, Rob, Froggatt, Antony and Wellesley, Laura. Livestock – Climate Change's Forgotten Sector. s.l. : Chatham House The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2014.

8. The importance of reduced meat and dairy consumption for meeting stringent climate change targets. Hedenus, Fredrik, Wirsenius, Stefan and Johansson, Daniel J A. 2014, Climatic Change, pp. 79-91.

PHOTOS

All photos and videos unless otherwise credited are taken by Vijay Shah, Antony Jinman or Duncan Eadie.